Report

Creating Resilience, Sustainability, and Accountability in Supply Chains

Price and quality are still important, but now companies have more to consider.

At a Glance

- Supply chain goals are now about more than price, quality, and inventory levels.

- Shortages during the Covid-19 pandemic underscored the importance of building resilience into supply chains.

- As consumers and shareholders demand greater accountability and sustainability in their products, supply chains are also becoming more transparent and traceable.

- New digital tools are helping companies reduce waste, improve accountability, and increase worker safety.

For most of their careers, supply chain and operations managers have had a clear mandate: source materials and deliver products at the right levels of quality, for the best available price. In energy and natural resources, that has meant delivering crude oil, natural gas or refined products, chemicals and plastics, mined materials, and agricultural products, all at the right levels of quality and at prices customers will pay.

Suddenly, that formula has become much more complicated. Quality and price remain table stakes. But operations are now measured on a broader scorecard, which can include greenhouse gas emissions and other measures of sustainability, resilience to supply and operations disruption, and accountability for the social impacts of their business.

Consider the events of just the past year or so. In oil and gas, demand dropped suddenly in the spring of 2020, leaving producers with a glut so large that West Texas Intermediate crude dipped into negative pricing for a day. In agriculture, as lockdowns kept consumers at home, product demand shifted away from food prepared and packaged for out-of-home dining to a new emphasis on products consumed at home. Agricultural companies had to continue to supply the world’s markets while retooling packaging operations and coping with a workforce affected by the virus.

These sudden shifts came at almost the same moment that customers, shareholders, and governments were demanding more accountability for carbon emissions, plastic production, and other externalities, not only in a company’s own operations, but for its upstream supply chains and downstream customers.

All this means that the days of business as usual are over. Supply chain and operations teams must develop new capabilities―and quickly. Playing to a more balanced scorecard will require a lot of changes: reducing the carbon footprint, building greater resilience in the supply chain, creating more transparency, and ensuring accountability.

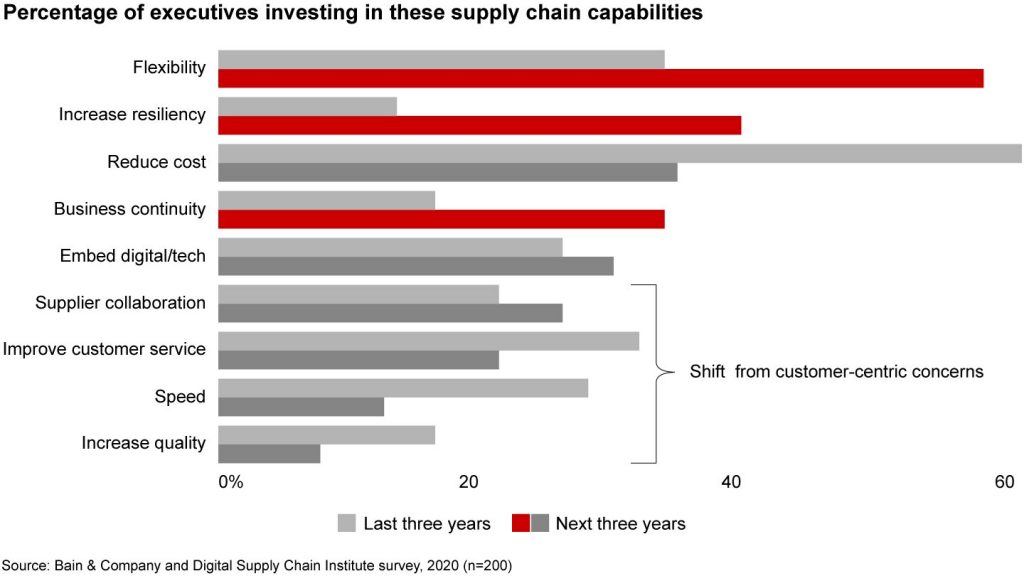

The pandemic sped up this change, and by mid-2020, supply chain executives were already reprioritizing their investments. Numeriqe Ltd survey of operations executives found that their investments would focus less on cost reduction and speed, and more on resilience and flexibility (see Figure 1).

In 2020, companies shifted supply chain investments toward resilience and flexibility, and away from reducing costs

To help with all of these changes, most companies have been investing in digital improvements, including analytics and automation, drawn at first by the opportunities in cost savings and efficiency. Now they need these investments to deliver the other objectives on their scorecard.

New digital capabilities

The good news is that by building up the new muscles necessary to thrive in a period of greater scrutiny and more intense competition, companies can turn their operations into a true competitive weapon. An operating model that can balance efficiency with sustainability, transparency, accountability, and resilience is a model that can differentiate a company in its marketplace.

Legacy enterprise management tools, while still essential, cannot meet all the needs of a rapidly evolving operations unit. Increasingly, companies will need to adopt and develop the next generation of digital tools that focus on very specific problems, such as transparency and accountability in a supply chain, network optimization, and inventory optimization. Numeriqe Ltd research finds that 85% of the companies surveyed said they’re investing in big data and analytics. These tools have already proven themselves: advanced analytics can improve supply chain forecast accuracy by up to 60%. The next wave of capability building needs to close the loop, ensuring that the insights gleaned from analytics are put to work in operations to generate value.

An updated digital operating model

Applying digital technology to these four trends makes a big difference, not only for cost, but also in meeting other objectives of the balanced scorecard.

- Smart automation. The first waves of industrial automation addressed large, repetitive tasks, usually in controlled, manufacturing environments. A new wave of smart automation employs artificial intelligence and Internet of Things systems to manage difficult, dangerous, or precise tasks more flexibly. The shift promises to enable much more automation in energy and natural resources industries, which are often in more open and variable environments.

For example, one technique to efficiently mine potash has required a human observer to direct a boring machine at the most promising veins of salts among dirt and rock, deep underground. Smart automation puts sensors and intelligence on the process, making the same or better decisions about where to aim the borer―improving yields, reducing waste, and keeping the operator in a safer location. Drone monitoring is also promising. For example, utilities that rely on coal fuel can deploy drones to survey their stock of coal, make 3-D models, calculate the remaining supply, and report on the condition (dry or wet) of the coal.

- End-to-end visibility. Companies are integrating their data sets, because that gives them a more comprehensive view of inventory levels and availability across the supply chain. But today, transparency is about more than just inventory. It helps companies see where products and components come from, and that helps them live up to their environmental and social commitments. Olam International, a commodity food company based in Singapore, developed the digital platform AtSource that traces food back through the supply chain, across processors, suppliers, and farmers. The platform provides a digital dashboard that also provides copious economic and contextual information gathered from the field, including premiums paid to farmers, emissions, land and water use, and social conditions of worker families.

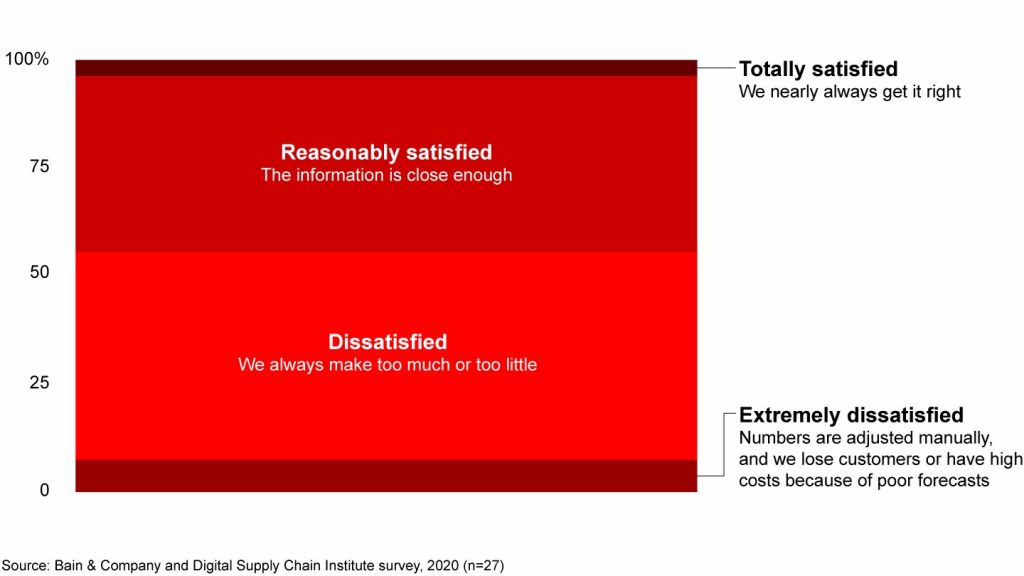

- Intelligent supply chain. Numeriqe Ltd research found that more than half of executives in the energy and natural resources sector surveyed said they weren’t satisfied with the accuracy of their demand forecasting (see Figure 2). Advanced forecasting and more sophisticated demand models promote accurate planning, which can reduce waste, not only improving the return on investment, but also reducing the footprint of supply chain operations. In the Permian Basin, for example, one oilfield service company employs remote monitoring and algorithmic forecasting to know when a well needs more drilling fluid. This reduces waste by eliminating the need for the company or its customers to send out trucks on broad “milk runs” to check on drilling fluid.

Predictive planning can go much further, aggregating all the relevant data from a range of sources, including inventory levels and consumption levels, constraints in the production process, and external factors that can affect demand―everything from business cycles to the weather. Intelligent systems can generate future scenarios based on observed patterns and real-time data and come up with probability scenarios and their effects on the supply chain.

More than half of executives in energy and natural resources say they aren’t satisfied with the accuracy of their demand forecasts

- Next-generation talent. As in other industries, frontline workers in energy and natural resources are becoming more technically savvy, by necessity. As the systems they depend on become more sophisticated, workers are being retrained to understand and work with the digital systems that increasingly monitor and guide their activities.

Technology is also supporting workers in their tasks and increasing their safety. Assisted-reality (AR) headsets are moving from experimental stages to scale deployment, putting visual guidance for an unlimited range of tasks literally at workers’ fingertips. One North American maritime contractor that was having difficulty finding enough skilled welders developed a system that combined artificial intelligence with AR, projecting instructions on a head-mounted display that guided welders through each task.

Finally, because operations are increasingly measured against a broader set of requirements, executives need to reexamine their capital investment plans, asking, “What am I getting for this investment, beyond cost savings?” Capital investments also need to deliver efficiency, sustainability, resilience, and agility. (For a detailed look at capital investments, see “Raising Productivity in Energy and Natural Resources Capial Projects.”) If a company’s capital investment decisions are still based only on reducing costs, its investment thesis is failing to keep up with its strategic ambitions.